When the Church fails - will the Government intervene?

- Anglican Futures

- Jul 5, 2023

- 16 min read

Updated: Aug 12, 2024

Last week, it was announced that having failed to put its own house in order, football’s FA Premier League would be made the subject of a government-established regulator.

The Premier League clubs are said to be worth a combined £24 billion and generate a combined income of £5.5 billion a year (but make total profits of only around £500 million).

The total attendance at each round of Premier League matches is about 800,000 which requires the League and its members to employ directly approximately 12,000 people.

Such is the might of the competition that the Guardian newspaper’s sub-headline was, “Observers expected the Premier League to snuff out any changes in the back rooms of Westminster but this has not come to pass”.

According to the government the regulator is necessary, “… to ensure that English football is sustainable and resilient, for the benefit of fans and the local communities football clubs serve”. The Premier League is owned by its autonomous twenty members, with a special share owned by the Football Association (FA) which has, up till now at least, enabled the FA to control appointments to its Board of Directors. The FA should be celebrating 160 years of governing the game this year. Instead, where the oversight of the member clubs and Football Association has failed, the government has stepped in.

The regulator will address: financial stability- clubs having a sustainable business model- that takes account of scenario planning, multi-year forecasting, monitoring and reporting, fit and proper leadership- “ensuring good custodians”, supporter interests, fairer distribution of wealth and the threat of “breakaways”.

Church of England v Premier League

The Church of England is worth at least £16 billion - the Church Commissioners manage about £10.5 billion of assets and all the member dioceses together own another £6 billion (although there is huge inequality of distribution). “Gate money” is only about £0.5m and total parish income only about £1.1billion but the Church’s total income is about £2 billion. It is fair to say that the Church doesn’t pay its people as well as the Premier League and its clubs do!

There is some scope for debate but average attendance in the CofE is a probably a bit lower than, but not dissimilar to, that in the Premier League, and of course the Church fills rather more seats each year, because it stages rather more 'fixtures'.

Direct 'employment' by the CoE is probably higher than for its football equivalent (about 8,500 stipendiary clergy and ordained clergy in 'other posts' plus diocesan staff) and while Premier League supporters are often fanatics, they do not begin to contribute to the cause as volunteers, to anything like the extent that fans of the CoE do. Active, but unpaid, clergy alone in the Church number around 12,000.

Sometimes the Premier League is thought to be a Wild West of bad leadership and governance, great riches but unsustainable finances, immorality, horrendous wealth inequality, sex scandals and endless infighting, without a shared vision of the future or even of what matters most and with the constant threat of some 'declaring UDI' and setting-up in competition.

The Premier League is a massively influential, wealthy, national institution, of very great importance to many people in all areas of the country, whether they be active attendees or more passive observers and is the subject of global attention. So, again, not unlike the Church of England, although the Premier League only has to co-ordinate the diverse interests of twenty essentially independent outfits, to the Church’s forty-two.

And displays of pomp, politeness and piety cannot hide the fact that to many the Church of England resembles the Premier League rather more than the kingdom of heaven.

The state of health of the established church

In justification of such a claim there follows something of an overview of the state of health of the established church as it has presented itself in recent days.

Safeguarding - Independent safeguarding Board?

In the face of all manner of growing safeguarding scandals, including in the “success stories” of the church, last week the Church of England’s Archbishops Council (AC) disbanded its, supposedly, “Independent Safeguarding Board” (ISB). The ISB was established following the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse’s (IICSA) finding, in 2020, that the CofE was a, "hiding place for sexual abusers", and that the Church had prioritised its reputation over the wellbeing of victims and survivors.

It might be thought that having been set-up in the wake of such devastating findings of failure, the AC would act with extreme caution in relation to the ISB, and victims of the Church. But, as one survivor has chronicled, almost certainly with the motive of getting rid of the independent members before Synod meets in July, they instead proceeded hastily and harshly.

The sacking of the ISB has attracted all but universal opprobrium. It seems that they were much too, “independent”, for the taste of the Council, who by their action proved they were anything but. (The history is well summarised in the, sadly, now defunct, The English Churchman).

To say that the former ISB and its supporters, and the AC and its (few) supporters are in a bitter conflict, does not begin to do justice to what is going on. The independent members have launched their barrage (summarised here) and the Archbishop of York, no less, has hit back. According to him, the independent members caused their own sacking, something one of them, the survivor advocate, Jasvinder Sanghera, called, "a lie". That should take the breath away - a victim of abuse calling the Archbishop of the Northern Province a liar - but sadly, so low are the expectations of the Church of England’s senior leadership, that it is passes almost unnoticed.

Stephen Cottrell advanced the extraordinary position that the Board had to be disbanded, against its wishes, because it was not independent enough. While he did have the good grace to accept that this was a “paradoxical” stance, he then made the even more risible suggestion that he, an archbishop, could “mediate” between the Archbishops’ Council and the ISB. His BBC interview was widely regarded as a Public Relations disaster.

Safeguarding - episcopal reputations

Cottrell was a strange choice to be the Church of England's second most senior overseer because he has his own disastrous safeguarding history, his “governance” in his previous episcopal role left the Diocese of Chelmsford in crisis without it being able to retain clergy for financial reasons, and due to his famed approach to 'pastoral care' of those who dare to disagree with him (examples can be found here and here).

If Stephen Cotttrell really is the second best leader in the CofE, the future is not bright.

The Church’s own man in parliament is being asked, “What on earth is going on?”. The MP's concern is perhaps unsurprising given that the bishops don’t even begin to agree amongst themselves - the Church’s deputy head of safeguarding, the Bishop of Birkenhead, Julie Conalty’s message could not have been more different to the strident and bullish one of Cottrell.

Note: that is a junior bishop disagreeing with her Metropolitan, that is to say, her “boss”, because she doubts his approach to the issue of the protection of children and vulnerable people.

And then the Bishop of Dover, and former chaplain to the Commons’ Speaker, Rose Hudson-Wilkin, thought it wise to use the BBC’s “Hardtalk” programme to openly disagree not only with her own deputy head of safeguarding but with the respected and independent safeguarding expert, Andrew Greystone. That is “hardtalk” indeed to the ears of survivors.

As if this was not confusing enough, having been silent for nearly a fortnight the Bishop for Safeguarding, Joanne Grenfell, stepped into the fray. She sided with the Archbishops' Council and claimed that the dispute notice issued by two members of the Independent Safeguarding Board, which should have triggered independent mediation, confirmed to her, "that we’d reached a point where relationships had broken down to the point where it wasn’t actually in the best interests of independence or scrutiny or survivors to carry on as we were."

And despite the best attempts of many, and the demands of survivors and their advocates, it seems that so far Synod has been unable to to prevent the Archbishops, and their Council being manipulated by vested interests. It remains to be seen whether lay member, Gavin Drake, can succeed in creating space for a proper debate this summer, or whether a procedural motion will be used to silence Synod, as was done in February 2022.

While the present Archbishop of York is at war with survivors and safeguarders, his predecessor, John Sentamu has been forced by the Church to step down from acting as a bishop due to his own failure in dealing with child sexual abuse and, in particular, his extraordinary reaction to the criticisms made of him in the Church’s own report.

Quite why Sentamu and other bishops receive one form of sanction or another while the equally egregious behaviour of the serving Bishop of Oxford, Steven Croft is met with no such action remains an unsolved mystery- it seems that there is one rule for some bishops and another for others.

Calls for government intervention

The Church’s refusal to deal with the Bishop Croft situation means that the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards has been asked to get involved in the hope that at least parliament can do something of what a Christian church refuses to do. Again, parliament is watching the failure of the historic governance.

Likewise, because, in their view the Archbishops’ Council, “…have shown that they are not fit to manage church safeguarding. It's time to take safeguarding out of their hands,” survivors of abuse, “… are calling on the Charity Commission to intervene and ensure that a truly independent body is set up that survivors can trust, without interference from the church.”

There is rarely much common ground between the bulk of the Church of England and the National Secular Society but on this, at least, there seems to be agreement.

Following these calls for the Charity Commission to intervene the Archbishop's Council have now reported itself to them,

“In line with our guidance, the Archbishops' Council has reported a serious incident in relation to these matters. We will engage with the trustees to determine whether a regulatory response is required".

This is not the first time in recent months that those concerned about the inability of the Church of England to regulate itself even in something as important as safeguarding have turned, for want of any other, mechanism, to the Charity Commission.

The Government’s guidance to charity trustees is clear that protecting people and safeguarding responsibilities "should be a governance priority for all charities". All charity trustees, "must take reasonable steps to protect from harm people who come into contact with your charity." It is woeful that the established Church, of all organisations, charged as it is with living out the compassion of Christ, might be falling foul of the basic expectations of the Charity Commission and need them to show them the way.

A Church of England spokesperson has said,“Our safeguarding responsibilities are a governance priority”. Which rather begs the question of how good then the Church’s governance is in areas that are, rightly, not such a priority.

And that is 'just' safeguarding, although, in fact, it isn’t. As Martin Sewell, a leading independent safeguarding expert, said in pointing all his fellow members of Synod to the English Churchman article,

“This is no longer just a safeguarding matter: it is a full bloodied crisis of governance with serious allegations of impropriety against both the Archbishops’ Council and the Secretariat of which The Secretary General is the executive head”.

The Archbishop of Canterbury's "personal failure"

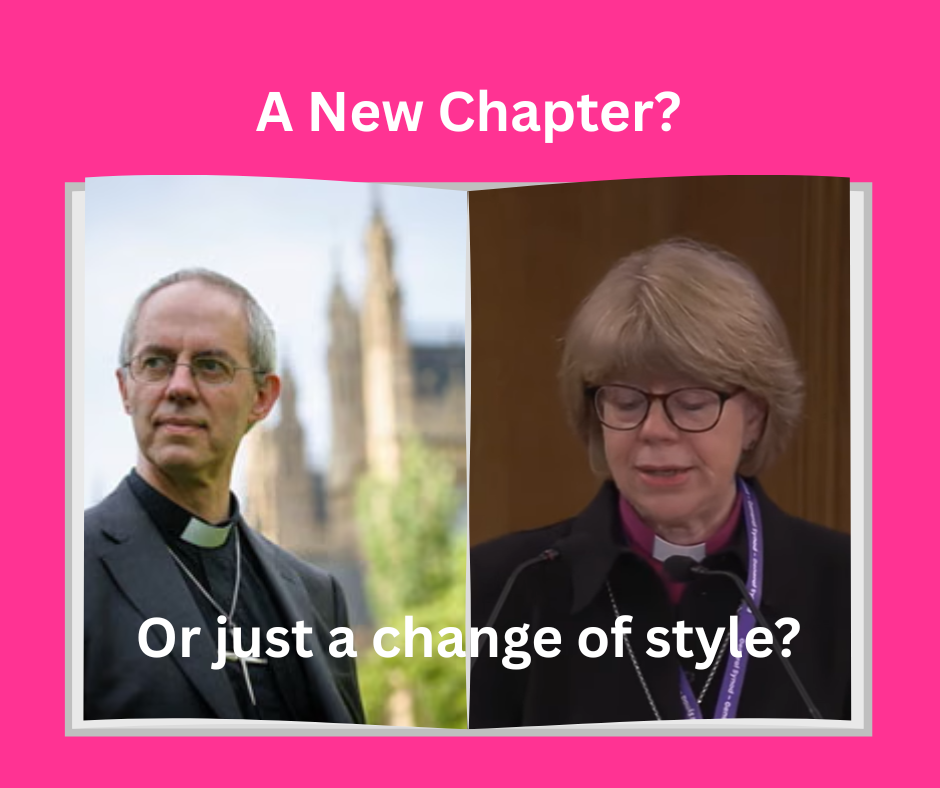

All this was going on the week after the Archbishop of Canterbury accepted that the decline of the Church on his watch was his "personal failure”. His honesty and humility may be to his credit but it is hard to imagine the Chair of the Football Association accepting personal responsibility for the loss of a third of fans without their role at least being under extreme scrutiny.

Justin Welby also believes that throughout his decade-long tenure there has been a failure of strategy. According to him, over the last 10 years there has been not enough focus on, “…the little, the local, the ordinary parishes” and too much on, “flagship projects”. Addressing this would mean, “… stopping the business of closing parishes and spreading clergy ever more thinly but being more open, I believe, to the ordination of those who are the natural community leaders and who are faithful Christians, so that we aim back towards many more parsons in the parish particularly in the rural areas”.

That is something, which, in theory at least, there could also be some agreement upon within the Church. The Save the Parish’ (STP) campaigners would whole-heartedly concur, but many on the ground, and in the STP, believe that the exact opposite is happening and happening without proper consultation and through too much centralised control.

On top of this, the Unite trade union has, on behalf 2,000 clergy and lay officers of the Church of England, put in a pay claim for a 9.5% rise. This is not a complaint about a lack of footballer-type wages but Unite claiming that clergy are among “the working poor”.

Overall, there is considerable resentment that while the Church Commissioners have their £10.5 billion in assets, mostly originating with parishes ,those parishes and their clergy are as explained, (ironically by a member of the said Archbishops’ Council), in dire financial straits.

It seems that the bishops’ inability to manage their own safeguarding responses, provide a workable church growth/decline strategy, address the grievances of their clergy and parishes and to lead well in virtually anything, does nothing to prevent them from believing that more centralisation and control by them can be anything other than a Good Thing. The Good Thing, however is itself leading to parish clergy revolting against such managerialism by the bishops.

Clergy Discipline Measure

The Clergy Discipline Measure still remains unreformed despite, if a word association game was played, the “CDM” being closely associated with the words, “disaster” and “car crash”. As Dr. Josephine Stein explains,

“Put simply, both the CDM and the Church’s responses to disclosures of ecclesiastical abuse are incompatible with Christian discipleship. Not only is the CDM time-consuming and expensive, the human cost can be hell on earth. The adversarial, legalistic approach causes structural damage to the relationships between bishops and clergy, between clergy, church-goers and congregations, and between the faithful and the Church itself. Some survivors and clergy lose their faith; some their very lives. The CDM is a disaster for the life of the Church.”

The CDM’s replacement will get its first airing at Synod in February but how any bishop can presently credibly “discipline” their clergy when, in so many areas, their own house (sometimes literally) is anything but “managed well”, is difficult to see. It is even harder to see when, apart from the potentially rather self-serving mantra of, “walking together”, they appear to agree on very little, as to what is right and wrong, either doctrinally or practically. Whether it is transgender archdeacons or Extinction Rebellion and the Red Rebels doing bizarre things in Bristol Cathedral, widespread cathedral gin and rum festivals (St Edmundsbury, Manchester, Newcastle), or repeated Islamic prayers (Blackburn, Manchester, Newcastle), there appear to be no policeable boundaries. Perhaps this is why clergy break the rules with seeming impunity.

Even disputes supposedly settled 30 years or a decade ago by agreements to “walk together”, are anything but resolved. In fact, they too are turning into open warfare between factions, with the bishops seemingly powerless to act to impose any restraint. The campaign group “Women and the Church” (WATCH) assert that the existing arrangements with regard to female clergy must be abandoned because,

“The Church of England, as the country’s established Church, has the opportunity and responsibility to take a moral lead in ensuring the human rights of all people are protected. Women’s rights are human rights, and our Church cannot advocate for human rights while it has institutionalised discrimination against women and other groups – which legitimises sexism and sometimes abuse.”

On that analysis the Church of England is amongst the most awful and disreputable organisations in modern society, and yet nothing is done. On the alternative analysis, the CofE is no longer fully part of the “one holy, Catholic church”, and yet nothing is done. About that either. Those aren’t reconcilable visions for the future of the organisation, even on something as basic and fundamental as gender roles.

Global Anglican Communion

In May, the Archbishop of Canterbury lost the global Anglican Communion - the one thing he has said he would sacrifice establishment for. Having lost the greater prize of the Communion, the logic of retaining the lesser prize of establishment, is not exactly compelling. And the (perceived) failings of the Church of England always attract calls for disestablishment, although, apparently, the Archbishop of Canterbury is “not remotely” worried about that.

Living in Love and Faith - infighting

All this mayhem is taking place in the much broader context of the shambolic and so divisive, Living in Love and Faith process, which was supposed to be concluded in July, but is apparently now postponed to November, allowing five more months of infighting.

So dissatisfied are they that the Church of England Evangelical Council (CEEC) are threatening something that falls somewhere on the spectrum between structural separation in the Church and schism.

Others are not waiting and have already started to implement their defiance - speaking of their own bishop and the whole House in ways like this, pulling their parish share by way of protest, or creating their own enclaves and immediately in so doing putting themselves at loggerheads with their bishop.

From the other side of the debate traditionalists are accused of deploying a, “… pernicious and yet all-pervasive narrative of victimhood” and being “asinine”, “dishonest”, part of a “… wicked, immoral consensus” and the “… ratcheting up of confected terror”. There doesn’t seem to be much of an agreed view as to a shared harmonious future between those who disagree in that but, yet again, it seems anything goes.

Those for whom the LLF proposals are not 'progressive' enough, again want parliament to take on the Church of England.

With much seeming justification, traditionalists are suggesting that the archbishops are abusing their power by using a device to force through change on matters of sexuality. One respected and knowledgeable commentator has said,

“… the issue now isn’t theological at all. Folks do need to grasp that. It is all about legalities, abuse of power and process. It is like old Boris Johnson trying to prorogue parliament when it was not going to vote for his particular Brexit plans, which the High Court had to reverse. If the elected representatives aren’t doing what you want, but you ‘know you are right’ you bypass them.

“In this case the attempt… by the archbishops to bring major change is clearly without precedent, not the intention of the canons, and if done would allow any future archbishops to make substantial change to the church by diktat…

“While in a sense this is about LLF it is now really about whether the church is redefined so bishops decide doctrine which is contrary to the CofE practice for 500 years, and now even more extreme whether a group within the bishops/archbishops’ ‘an elite’ can decide it and impose it on the church. Thus, it is really now about good governance and power in the church. If power shifts to an elite/centre/the Anglican popes on this, then it will remain there for every other issue too.”

The General Synod is a creation of parliament, and the Canons are the law of the land, and yet it is suggested that the archbishops, of all people, and their 'elite', who have failed so conspicuously, in so many areas, are responding by making a naked and ultra vires grab for even more control. If defying the intent of parliament is not a genuine crisis in governance, especially given the long-term implications for any proper order and accountability in the Church, it is hard to imagine what is.

A break-away rival is also there - not just in the threats of the CEEC - but in the creation of the Anglican Network in Europe. This may not offer riches like a European Super League, perhaps, in fact, rather the opposite, but it does have the sponsorship of the vast majority of the world’s Anglicans. That the Global Anglican Futures Conference (Gafcon) has seen it as fit and necessary to provide an alternative Anglican jurisdiction in Europe should tell anyone connected to the Church of England all it needs to know about the state of the global reputation of its 'brand'.

CofE - Broad Church or a Lawless Church?

There is a difference of real substance between being a broad church and a lawless one.

That men and women, clergy and laity, from just about the full range of ecclesiology and every part of the Church, Christians and secularists agree that the church is abysmally governed demands change.

Amidst all this is the additional unspoken failure - a total lack of clarity as to what purpose the Church of England exists and what it is fundamentally about; there being a presence (in theory) in every parish; acting as heritage and historical reenactment society; doing theology; being in parliament; being in the public square; addressing perceived historic injustices; supposedly leading the Anglican Communion,. Then there’s the Archbishop of York’s priority of being “simpler, bolder, humbler”, which is a strategy so far from simple that it can only be explained in about 90 jargon laden words, and a diagram like the one below:

On the other hand the Archbishops' Council has seven overlapping but distinct objectives, while the Church of England prioritises Net Zero within seven years, at the same time as trying to grow the size of church.

The existing leadership of the Church of England have proved totally unable to ensure that the man or woman in the street could articulate why it matters at all.

The question is whether the Church of England can reform itself so as to exhibit at least a semblance of good leadership and governance, to use its great wealth to establish stable finances, to root out immorality, horrendous financial inequality, sex scandals and endless infighting, and establish a shared vision of the future, or even what matters most, so as to stop losing its fanbase, and avoid the constant threat of more “declaring UDI” and establishing a viable rival.

That is something the government may not only be interested in, but arguably has a legitimate interest in, and not only because of establishment. The Church of England is custodian of about 45% of all Grade 1 listed buildings.

It is unlikely that any government would want to take on over 12,000 listed buildings, should the Church not be able to care for many of them.

Moreover, like the Premier League, the Church of England has a historical, international, national, and local significance that runs deep in many lives and communities.

To some shades of government, intervening in the name of equality, diversity, tolerance, inclusion etc would itself be attractive. And the lack of safety from sexual abusers IICSA identified might even make it imperative. The government cannot allow such an institution to functionally ignore the IICSA report.

The Church leadership may feel that their best hope of being left to it, is that a government would consider the CofE relatively unimportant compared to football, or too difficult to reform and regulate. But in the light of the various facets of the government’s legitimate, and even necessary, interest that have been identified, it seems improbably for the CofE to be allowed to continue unhindered, in an ever more dysfunctional way.

That the Church can reform and regulate itself, however, seems improbable. The quality of the College of Bishops does not appear to be equal to the task, and the pool from which it is chosen shrinks in size and depth all the time. If Synod, the Archbishops’ Council, the College of Bishops, the Communion and the lobby groups can’t bring order and discipline (and often just fight each other), then it is hard to see what can do so, other than some external intervention.

The same fate as the Premier League

It might be wondered whether there is any good reason for the established Church of England not to suffer the same fate as the Premier League. All the more so if, by claiming to speak from the moral high ground, it continues to lay came to a level of trustworthiness which is unjustified, and even, unsafe.

The Church could hardly complain about others taking it in hand when, even in the week of the ISB fiasco, it has patted itself on the back for acting against large organisations it deems to have made, “not nearly enough progress”, to reform themselves in the manner the CofE would like them to.

The book of Judges famously tells us that, “In those days Israel had no king; everyone did as they saw fit”. Everyone doing what was right in their own eyes doesn’t seem to be too inaccurate a description of the state of the Church of England.

And so perhaps God will use the Philistines to bring a wandering Church back. Or maybe he will bring temporary, if cruel and chaotic, relief under a 'judge'. But if a king is imposed that will not go well either. And therein lies the rub: Erastianism is as fatal to the church as lawlessness.

Surely a major issue is the way in which the Archbishops' Council is constituted? There are 19 people on it, including the 2 Archbishops and 7 (yes SEVEN) people appointed by the Archbishops. It seems likely that, on any controversial matters, all the appointees and the 2 Archbishops will vote as a bloc, meaning that they only need 1 of the remaining 10 people to vote with them for the Archbishops' views to prevail. This is neither democracy, not is it episcopal oversight - it is instead managerial oligarchy, if not dictatorship.

It is therefore not surprising that such a council does not understand the meaning of the word 'independent', which has led to the disastrous sacking of all the…

LLF is clearly a complicated issue and sincere faithful Christians have genuine disagreements about how we are called to show Chris’s love to the world.

However there is still more sense in this AF article and in an Eastern Eye article (referenced below) than all the combined output of the entire Archbishops Council put together over the last 8 years.

The governance of the Church of England has become a huge issue after all the failings of those 8 years.

GS has been incredibly supine up to now.

Will it ever hold the leadership to account?

https://www.easterneye.biz/exclusive-church-victimises-whistle-blowers/

Very significant that the Church refused to respond to the Eastern Eye article.