"Variable Geometry" - the new good disagreement?

- Anglican Futures

- Feb 24, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 12, 2024

The Archbishop of Canterbury chose to riff on some familiar themes in his Presidential Address to General Synod. The first was the danger of ‘fear’ – this time in the context of ‘suffering’ and ‘enemies’; the second was the need for the Church to deal well with internal conflicts, “if we are able to minister effectively externally to our nation and world”.

A quick survey of his Presidential Addresses shows just how familiar it all was.

Fear of the other

Fear of ‘the other’ is the cardinal sin according to the Archbishop – it causes people to form “self protecting, and reinforcing huddles” (2024); to meet in “a hermeneutic of conspiracy” (2015); to act like a “dysfunctional crew heading for the rocks, different groups all strive to grab the wheel” (2016). Fear is the “greatest enemy of dialogue” (2016), which “encourages a bunker mentality” (2018) and “make[s] a lion out of shadows” (2020).

This year, Archbishop Justin challenged Synod saying, “The fear and suffering that come from division make us look at other people as our enemies and we have to resist that illusion in faithful and honest community. Causes of fear, which leads to a sense of enmity are well disguised as uncertainty, unpredictability and uncontrollability of life and like barnacles on the hull of a ship, they attach themselves to make us see other people as our enemies, and that is the devil's work.”

The prize of visible unity depite functional diversity

If fear is the cardinal sin – then finding a way to deal with the Church’s internal conflicts is the prize, as he explained in his first Presidential Address in 2014 - “There is a prize, the quest for which it is worth almost anything to achieve. The prize is visible unity in Christ despite functional diversity.”

Back in 2014, the answer was, “facilitated conversations” and "gracious reconciliation". His aim was for, “a church that speaks to the world and says that consistency and coherence is not the ultimate virtue, that is found in holy grace.”

In 2015, he encouraged Synod to be ‘untidy’ – “Human beings, being sinners, will never be tidy in the way they disagree, or in the nature of their relationships….Untidiness in relationships is normal, not fearful: it expresses the richness of who we are.”

2016 was the year when he claimed the Primates agreed to “Walk Together” – embracing “unity which relishes and celebrates the diversity of freedom and flourishing within broad limits of order.”

In 2017, just a few weeks after a General Election, Welby turned his eyes outward and called on Synod to “reimagine Britain” and “seize the best future that lies before us.”

But the problems hadn’t gone away, so 2018 was all about “Faithful Innovation”, and in 2019 his concern was the balance in the Anglican Communion between the “right” to autonomy and the inter-dependence, which “should limit that right out of love for one another”.

In 2020, the Archbishop spoke to Synod, before Covid struck, about “stepping together into God’s extraordinary project", praying for those with whom “we disagree” and loving one another, “with the love that ‘covers a multitude of sins".

Such positivity appeared to have waned somewhat by 2021, when he welcomed the new Synod, with the warning that “any synod that ceases to walk together, that gets stuck in one place ceases to be a synod". In that year’s joint presidential address he explained this meant Synod was called “to model disagreeing well".

As he looked forward to the Lambeth Conference, in 2022, the Archbishop of Canterbury was focused on “the common good”, through which the Church would realise, “we are not a church of loss and gain, factions in a zero-sum struggle, but of abundance and grace".

At the Lambeth Conference, he used the "messy family" anaology - with all the problems outlined in a previous blog.

In 2023, with the Global Anglican Communion rejecting his call to Walk Together, he turned to the Tower of Babel and its reversal at Pentecost to speak of “scattering” and “gathering”, and of a God, who, “gathers out of a physically and ideologically scattered people a church which acts in unity for those who are different, and does it with unquestioning love".

The Archbishop’s tenacity may be impressive. For more than ten years, and despite serious opposition, he has continued to repeat the same message. It is as if he is convinced of the Illusory Truth effect - that suggests repetition can make something true.

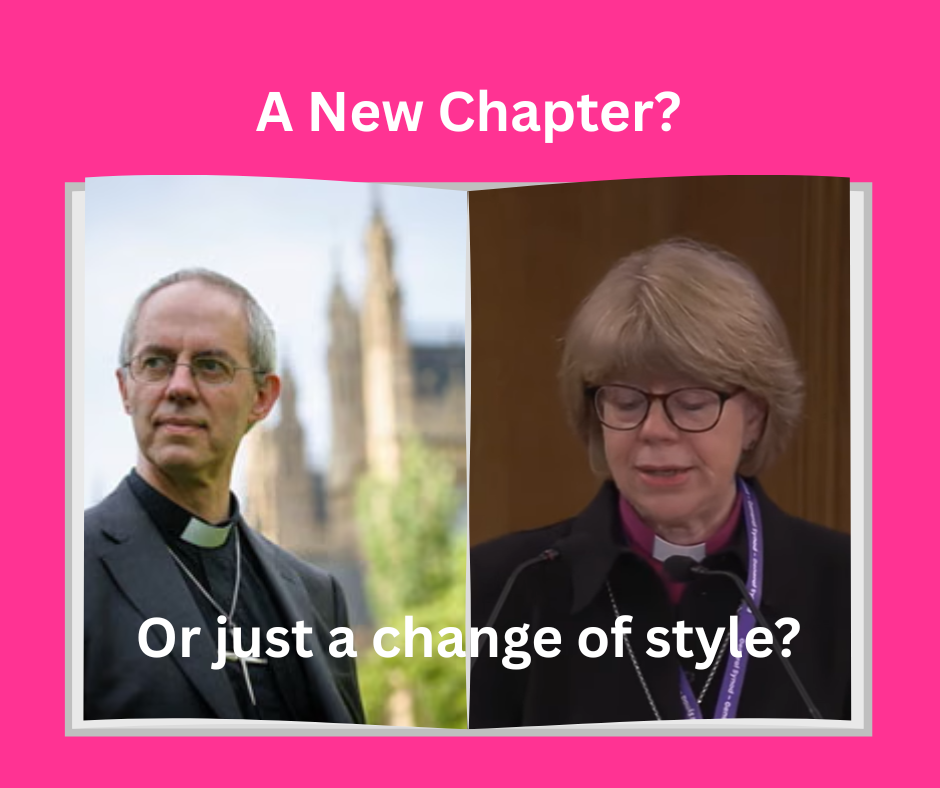

The language may change – but the goal remains the same. It doesn’t matter whether visible unity alongside functional diversity, comes through love driving out fear and covering over sin, or by walking together, faithful innovation or modelling good disagreement. Yesterday, he chose to look to the political sphere for a new solution, which he intends to put to those Primates of the Anglican Communion who are willing to meet with him in Rome in April.

“There”, he said, “we will look at what the communion could do to remain in a variable geometry of unity, but also an unvarying commitment of love in Christ. Those two expressions vary in geometry of unity and unvarying commitment of love in Christ offer us all a way forward in holy obedience to God".

The three parts of this new expression need unpacking:

"A variable geometry of unity...

The first part may sound like gobbledeygook but with a little digging it turns out to be relatively simple: ‘Variable geometry’ is a term that has been used in the EU and Africa to describe “the idea of a method of differentiated integration which acknowledges that there are irreconcilable differences within the integration structure and therefore allows for a permanent separation between a group of Member States [the Core] and a number of less developed integration units.” Depending on the political situation in each individual country, variable geometry (or multi-speed Europe) enables different parts of the European Union to integrate at different levels and pace.

Perhaps the Archbishop of Canterbury read the Anglican Futures blog ,“In search of “Formal Structural Pastoral Provision”, which used a similar ‘political’ model, based on the relationship between the Crown Dependencies and the UK, to describe a Non-Geographical Diocese in the Church of England - NoGeoDoCE.

It is possible to see at a pragmatic level how such differentiated integration may occur between the different provinces of the Anglican Communion – and even within the Church of England. Putting aside the ecclesial complications of describing these organisations as a ‘Communion’ or ‘Church’, it might be possible to maintain some historic, relational links and continue to share some practical services, while not assuming a common faith.

There is, however, one substantial obstacle. Variable geometry requires a core and a periphery to be identified. It is difficult to imagine either the progressive, Canterbury-aligned provinces, or the traditional provinces who are aligned with the Global South Fellowship of Anglicans (GSFA), giving up their ‘membership’ status and accepting the role of ‘less developed integration units’. But perhaps that is an argument for another day.

It is also possible that the Archbishop of Canterbury was actually thinking of the way engineers use the term 'variable geometry' - where the wings of aircraft change position depending on their context.

Whatever he means, the statement becomes more complicated in the second part.

... and unvarying commitment of love in Christ...

Pointing out another's sin can be loving. It can be a warning, it can cause, in the Apostle Paul's words, "godly sorrow" which "brings repentance that leads to salvation." (2 Corinthians 7:10)

Ignoring sin can be unloving. Jeremiah is scathing about the prophets who say, "Peace, peace, when there is no peace," and at the route of the problem is their unwillingness to recognise the sin of which they should be ashamed. (Jeremiah 6: 13-15)

If variable geometry led to a form of differentiated integration where sin was named and people were called to repentance that would be loving, but that does not appear to be the proposal being put forward by the Archbishop, as can be seen in the final part of his statement.

... offer us all a way forward in holy obedience to God"

The Archbishop of Canterbury assumes that both the progressive and the orthodox understandings of sexuality and marriage can be described as showing “unvarying commitment of love in Christ” and “holy obedience to God”, despite being diametrically opposed to one another.

And that is the problem. His quest for unity has led the Archbishop to a position where the ultimate expression of holiness is a Church which holds together completely contradictory positions on fundamental issues, on which the bible speaks clearly.

This is the view that Justin Welby sought to impose on the Lambeth Conference. It is also the view espoused by Bishop Martyn Snow in Living in Love, Faith and Reconciliation.

But this perspective completely rejects an orthodox understanding of the Scriptures – denying the historic, catholic, biblical understanding of creation, salvation and the eternal relationship between Christ and the Church. It is a conclusion that has been soundly rejected in the strongest terms by the majority of the Anglican Communion – represented by GSFA and Gafcon - and also by the Church of England Evangelical Council.

In their Ash Wednesday Statement in 2023, the Primates of GSFA could not have been clearer – saying that the Church of England’s decision to introduce Prayers of Loves and Faith was “a departure from the historic faith passed down from the Apostles".

If one considers the Anglican Communion, or the Church of England, to be merely a political organisation, ‘variable geometry’ may have some value. But, if they are ecclesial bodies, it is the very nature of the ‘irreconcilable difference’ which makes the ‘variable geometry’ necessary, that becomes the sticking point. Not everyone is walking in 'holy obedience to God'. There must be serious doubts as to whether those who have departed from the Apostolic faith can be described as being 'in Christ'.

Despite Justin Welby’s repeated claims, it is not ‘fear’ that threatens to divide the Church – but error – and very serious error at that. Recognising this should stop the Archbishop’s quest for visible unity in its tracks - because there can be no unity (whatever the geometry) until those who have departed from the faith, repent, and return to the Apostolic teaching.

But, on past form, the Archbishop of Canterbury will not be put off. He may already be penning his 2025 Presidential Address and Synod can make a pretty good guess at what he’ll say.

Perhaps print this off and hand out copies widely to Synod members. It is absolutely timely.

Thank you for the good analysis. Just a small note to say that “Canterbury-aligned provinces” are not all necessarily progressive. I can think of at least one province (and I suspect there are several others) which is staunchly orthodox, but not a big player like Nigeria or Rwanda, and which lives as a persecuted minority.

They are supported mainly by evangelicals in English link dioceses and experience encouragement and good teaching from visiting delegations. Visits from senior clergy (including the Archbishop of Canterbury) are deeply appreciated since it shows a commitment of time and risk of personal safety to come and encourage. They are not feeling pressured in any way to change their doctrine in marriage or sexuality, and see…

There can be no unity between truth and error or, to put it more bluntly, between God and Satan. Any pretence that there can be, by repeating lies again and again as Welby and Snow do, is only to invite comparisons with Goebbels - hardly a recipe for the message being pushed, and certainly no part of the true gospel.

This latest synod just feels like more shuffling of the deckchairs on the Titanic. The likes of the CEEC should be making plans for a real alternative structure like the ACNA, which can quickly ally itself to Gafcon and the GSFA. leaving the Welby rump to wither and die.

At least an end of all the talking about Church structures…