Anglican Myth 7: The Temporal/Spiritual Divide

- Anglican Futures

- Mar 29, 2023

- 17 min read

Updated: Aug 13, 2024

One form of ‘visible differentiation’ proposed in response to revisionism in the Church of England is for churches or individuals to declare a refusal to participate in, or identify with, the ‘spiritual’ parts of church relationships or polity. This temporal/spiritual divide is one way in which it is suggested that clergy might reject heterodox bishops while retaining the licence of that bishop and remaining in the Church of England.

Thus, the ReNew Movement have asked of congregations,

“For a bishop who does not uphold or defend biblical teaching (i.e. any bishop who refuses to state that they will not use the Prayers of Love and Faith, and/or refuses to uphold Canon B30, and/or refuses to reaffirm the rightness of sexual intimacy only within such marriage), will our PCCs explain to that bishop that their action means they are teaching falsely and thus are no longer welcome to preach, to confirm, and to ordain at our churches AND that we are unable to accept their spiritual oversight so orthodox episcopal oversight will need to be provided or will have to be sought?”

In the last clause the suggestion is not that the oversight of the diocesan bishop is repudiated in its entirety, but that it is only rejected in things ‘spiritual’. Thus, the bishop’s oversight of the church remains in things ‘temporal', while the ‘spiritual' oversight is sought from an alternative bishop (which in itself raises a number of other questions, that are discussed here).

The ReNew guidance gives this concept wide application, for example:

“Will we ask our clergy to avoid all or part of Clergy chapter meetings/clergy conferences if the agenda is more spiritual than temporal, and if a false teacher is leading or speaking? Will churchwardens not participate in similar services or meetings?”

In July 2019, the then chairman of the ReNew Conference[1] explained it this way to his church,

“The Church of England can claim validity and we should recognise it as valid on two levels. One, as a secular body; it owns a lot of property, it dishes out the property - an estate agent; a Golf Club, yeah, it's just a kind of secular body held together; Southwark Council. We’re members of all sorts of, you know, we’re part of the City of London - I was at a civic thing, one day this week for…something. So, it's a secular body. But it's also a spiritual body insofar as the Church of England holds out the gospel - but insofar as it doesn't well it's irrelevant.” (at 20 mins and 15 secs)

In other words, it is suggested that it is possible to have a relationship with the diocese which is merely temporal, just as with any other secular organisation.

This conception of denomination as potentially irrelevant is underpinned by a particular understanding of the local church, described in the same address, in this way,

“Listen to Article XIX… notice the singular,

‘The visible church of Christ is a congregation of faithful men [and women] in which the pure word of God is preached and the sacraments duly administered according to Christ's ordinance in all those things that of necessity are requisite to the same.’

The last part is actually redundant because if the word of truth, the Word of God is taught, the sacraments will be duly administered.

But the visible Church of Christ is a congregation of faithful men in which the pure word of God is preached. The church is not defined by institutional structures or historical lineages; whether a Bishop has laid hands on a Bishop, who's laid hands on a Bishop, who's laid on hands on a Bishop, who also inherited one of those stupid hats. Your Christian Union, your family, your Bible study group, your Sunday gathering, wherever people are sitting under the word of God they are, in one sense, a kind of nascent embryonic church. They’re part of the eternal church. It's a wonderful, wonderful truth.

Should we then simply exist in splendid isolation? Well, we’ll never be in splendid isolation because we're part of the eternal Church of Christ. We can never be in sort of splendid isolation. But in the Bible congregations do come together for the particular purpose of missionary enterprise governed by doctrinal truth”. (16 min 50 sec)

As such, just over two years’ ago the church announced that they were,

“… not leaving the Church of England and will remain a member of its Deanery and Diocesan structures for the most part. However [the church] will be withdrawing from those activities which indicate full spiritual partnership.”

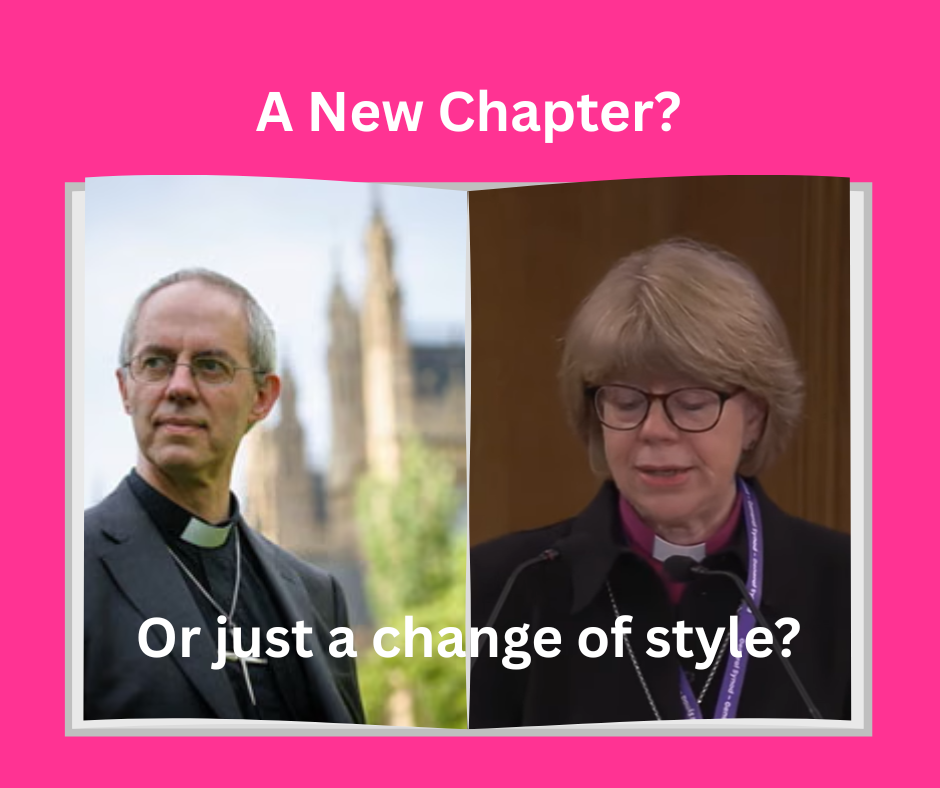

And then in January this year the church wrote to their diocesan, Bishop Sarah Mullally,

“We wrote to you prior to the completion of this process to indicate that steps such as you have taken will inevitably further affect our already broken partnership with the House of Bishops. We shall await the conclusion of the General Synod in February before seeking a conversation about the provision which will be necessary for those forced by your decision into having no acceptable episcopal oversight.”

Other churches in the ReNew network have done much the same thing; one wrote to their bishop saying,

“We shall not recognise the spiritual authority over our church of Bishops who promote, practice, or allow this false teaching.”

Again, it is just the ‘spiritual’ element of the oversight, not the totality, which is rejected.

Another wrote that their clergy,

“…have already declared that we are in impaired communion with the bishops in our diocese, which means that we will not welcome them to preach, confirm, ordain or conduct our ministerial reviews, and we will not take communion with them. The PCC has also taken action to ensure that any money we pay within the diocese is distributed via the Oxford Good Stewards Trust and is only used for faithful gospel ministry and essential administrative costs.”

Again, it is the ‘spiritual’ element of the relationship, that is being refused, whilst they are content to continue funding the ‘temporal’ administration costs. And so it was confirmed at the Oxford Diocesan Synod that the diocese would still receive the same amount of money from this church, even if is, perhaps, in part, via the trust.

The latest guidance from the Bishop of Ebbsfleet seeks to draw a similar distinction; this time between the ‘legal’ and ‘pastoral’ ministry of the Bishop. He writes.

“This ‘legal jurisdiction’ is distinguishable from the ‘pastoral ministry’ of a Bishop, as is evident in the +Ebbsfleet arrangements...”.

There are many and varied references throughout church history to some form of temporal/spiritual divided but to most British Anglicans the words are best known from whenever clergy are admitted to a new parish (collation/induction/licensing/installation). The ‘spiritualities’ (the responsibilities of conducting divine service, occasional offices, preaching etc.) and, if they are the incumbent, the ‘temporalities’ (the ‘legal possession’ of the church building) are dealt with separately. The former is the preserve of the diocesan bishop, as chief pastor of the diocese, and the latter that of the archdeacon.

How do these ideas work in practice?

As such the temporal/spiritual phraseology has a temptingly familiar ring to it. But the assertions above, adopting the concept (whatever the origin) raise the question, or rather questions, as to whether such a distinction, in some form, can apply to the relationship between an individual church or cleric and the diocese or bishop?

Questions plural because different issues arise in each (combination) of situations.

The Cleric and the Bishop

It has been observed before on this Blog, that the Canons of the Church of England state that the diocesan bishop is the chief pastor (Canon C18(1)) and principal minister (Canon C18(4)) of all in the diocese and that beneficed clergy share the cure of souls with him or her, while others minister under the bishops’ licence or PTO. This remains the case, whether, a cleric, seeks, or even achieves, the physical exclusion of the bishop from their parish or church building.

Therefore, the cleric’s Oath of Canonical Obedience requires them to accept this understanding of the bishop’s role, whether they approve of the current office holder or not. This is a point made in a recent report of the Faith and Order Commission of the Church of England,

“These relational obligations would still remain, even if the act of oath-taking did not occur…. However, in taking the Oaths, something important is happening. Ministers making a public promise, articulating basic obligations and committing to certain relationships – with the sovereign, the bishop and by implication, the whole church.” (Page 13)

Now, it is fair to say, that the report goes on, “the Oath of Canonical Obedience takes for granted that those in authority are themselves obedient to the Christian message as proclaimed in the Word of God.” (page 26), which raises the issue of what happens when that is obviously not the case.

Some have suggested that in such a situation, the legal obligation on the cleric to uphold the Canons does not include the need to acknowledge the current holder of the office as the chief pastor and senior minister of the diocese. They claim the oath is being made to the office not the person. In the Latimer Trust publication, The Oath of Canonical Obedience, Dr Gerald Bray sets out why this is not the case.

“Now there are several bishops who are prepared to abandon traditional Christian teaching, not only on matters of doctrine but also in the sphere of morality, and particularly sexual morality. There can be little doubt that the Apostle Paul would never have tolerated anything like that, or that he would have expected Christians not to associate with such people at all – let alone swear an oath of canonical obedience to them!” (Page 9)

Surprisingly, the Bishop of Ebbsfleet appears to disagree; his latest guidance seeks to separate the different functions of the bishop, arguing that a bishops’ signature on a licence is “clearly an expression of their legal authority rather than of ministry oversight.” This ignores the fact that the licence is only given after the taking of Oaths, which assume that the ministry oversight as set out in the Canons has already been accepted.

But oaths are only the beginning. An incumbent (and more so a Priest-in-charge) can only occupy the church building by virtue of their relationship with the bishop, and it is the bishop who ultimately polices breaches of the Canons and enforces Clergy Discipline.

While it may be true that it is possible for the diocesan bishop to delegate aspects of their pastoral and sacramental ministry to another bishop, such as the Bishop of Ebbsfleet, that delegation is by request not right, and the diocesan continues to be responsible for that ministry and can withdraw their permission at any time. It is worth noting the diocesan bishop does not delegate their role of chief pastor, or senior minister, in the congregations the Bishop of Ebbsfleet serves, any more than they do when any other suffragan bishop visits a parish.

The reality is the diocesan bishop’s functions are designed to be integrated – they pastor the diocese, in part by ensuring there are clergy to minister the Word and Sacraments to the congregations and to do that they need the legal powers of the Ordinary.

All things being considered, in what sense the relationship between the bishop and the cleric could be regarded as being merely 'temporal' or 'legal', is hard to conceive.

The ‘Local Church’ and the Bishop

It is too often forgotten that laity have and need bishops too. Canon C18 again:

“Every [diocesan] bishop is the chief pastor of all that are within his diocese, as well laity as clergy, and their father in God;”

In Anglican polity it is bishops who ought to protect the flock from heretical ministers and prevent the local congregation being otherwise mistreated, bullied, exploited or subject to an unholy leader.

An Anglican flock without a bishop offering that spiritual protection, is in a worse position than a congregational or presbyterian church. The latter two can dispense with the false teacher, by vote of members or the discipline of the presbytery, the former cannot. Such sheep are left with the alternative of staying where the Bible is unfaithfully taught (in word or deed) or leaving the church - neither is a choice they should properly have to make.

An incumbent, operating within an Anglican polity, who supposes that his or her people can do without the protective oversight of a bishop, because, of course they would never fall into error, is in a very dangerous place indeed, as are their congregation.

That all too few faithful Anglicans in England have experienced proper oversight in the past does not detract from the fact that it should not be so. It is not an exaggeration to say that the present crisis is primarily the product of failed episcopacy, as can be seen from the voting patterns at the February General Synod:

Only 28% of the House of Clergy voted in favour of retaining the traditional definition of marriage found in Canon B30,

63% of the House of Clergy voted against the proposition that “ministers should order their lives in accordance with the doctrine of the Church of England,”

56% of clergy did not want the House of Bishops to preclude the blessing of sexually active relationships outside heterosexual marriage.

Such ungodly views are first and foremost a failure of episcopacy over many decades. It could therefore absolutely be expected that the House of Bishops' votes on the same issues would be even more shocking, as indeed they were: 2%, 67% and 71% respectively.

The diocesan bishop is also responsible for safeguarding in every parish, a matter that most agree about and one that the Bishop of Ebbsfleet takes pains to point out. However, not least in the light of Matthew 18:6, a church that does not think safeguarding is a spiritual issue, has very serious problems. Safeguarding is the deepest of deep trusts - it is profoundly spiritual – surely no bishop should be asked to consider their obligations in that regard to be merely ‘temporal’ or ‘legal’, even if it should never be less than that.

The Cleric and the Diocese

The Church Commissioners pay clergy stipends but are reimbursed by the receiving cleric’s diocese. Clergy housing is, more often than not, provided by the diocese. Thus, only if the finest of distinctions is made, or in some very rare situations, can it be said that an individual cleric is not in a financial relationship with the diocese.

While money might be regarded as the ultimate temporal issue it is for that reason that the Lord regarded it as perhaps the most important spiritual signifier (Matthew 6: 19-24). Nothing reveals the heart like the individual’s (or church’s) attitude to money. It might be said that virtually nothing is more spiritual than money.

Most clergy would be deeply wary of accepting a gift from the local, who is known as a “notorious sinner” for his regular acts of dishonesty, however “spiritual” he was trying to be, and rightly so. Some may wonder about the extent to which taking the silver of a heretical diocese is very different.

The ‘Local Church’ and the Diocese

The quotation from Article XIX set out above is significant, because, of course, it only cites half of the Article.

The other half of the Article shows that the local church 'singular', being 'a congregation', is not the exclusive definition of “the Church,” by incorporating a wider understanding,

“As the Church of Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch, have erred; so also the Church of Rome hath erred, not only in their living and manner of Ceremonies, but also in matters of Faith.”

Accordingly, even on such a reading as advanced above, the Article defines “church” as both local “ekklesia” and the wider “Church” or “Churches”.

However, such a reading has been roundly rejected as a modern interpretation unknown in the sixteenth century.

“The reformers insisted on the priesthood of all believers, that baptism, not further, special vows, made a person a member of the “Church.” To show that distinction, Tyndale translated ekklesia with a new English word, “congregation.” You will see that word used in the Articles. It does not refer to individual parish families but to the unity of lay, religious and ordained in one body as the church.” (16th Century Anglican Ecclesiology – Ashley Null Page 5)[2]

It goes without saying that such a partial reading of half of Article XIX also ignores Article XX altogether. That Article describes “the Church” as the Church, at least at a national or provincial level, not just local,

“The Church hath power to decree Rites or Ceremonies, and authority in Controversies of Faith: And yet it is not lawful for the Church to ordain anything that is contrary to God's Word written, neither may it so expound one place of Scripture, that it be repugnant to another. Wherefore, although the Church be a witness and a keeper of holy Writ, yet, as it ought not to decree any thing against the same, so besides the same ought it not to enforce any thing to be believed for necessity of Salvation”.

The Articles are not Scripture. But while they sit firmly under Scripture, like the Book of Common Prayer and Ordinal (which also have so much to say on this topic), they also sit firmly over the individual Anglican’s own understanding. In truth, the Articles can either only be appealed to as a whole and in their true sense, or not at all.

It is also worth considering the practical aspects of the nature of the relationship between the church (local congregation) and the diocesan structures.

It is, frankly, problematic to see how the diocese being treated as merely a secular institution can work in both in a fashion that is both coherent and consistent.

One option, and practically the simpler, is for the church to 'silo' itself as much as possible - to treat the diocese with the same distance and disregard as many have for their local Council, until the rubbish is not collected.

To do that, of course, means not participating in synods and other structures of the diocese, and thereby leaving them to the revisionists. But even adopting such an approach, neither temporal nor spiritual separation can be by any means absolute. To take but four examples:

the local church still has to account to the diocese for fees for occasional offices and hand them over.

a quinquennial inspection resulting in the expectation of considerable expenditure steers the local church’s finances in the direction of the diocese’s assessment and priorities.

the local church must engage with the diocesan safeguarding policies and training.

if the local church wishes to see members ordained, they will need the support of the Diocesan Director of Ordinands.

A great number more examples, derived from long-experience of corresponding with their diocese, will occur to plenty of readers.

Many, churches, however, in accordance with the lead of organisations like the Church of England Evangelical Council, intend to pursue the opposite approach to 'siloing' themselves. They intend to be activists, by doing all they can to influence, even control, synods, Diocesan Boards of Finance, key committees and posts. At this point individuals will need to decide how to do this, keeping in mind the principals of the temporal / spiritual divide set out in the introduction to this blog.

One principle is to withdraw from activities that, "indicate full spiritual partnership”: while individuals may be fairly readily able to avoid communing as a mark of this broken partnership, how much else they can do consistently and coherently is a vexed subject. Two recent examples will suffice.

Just before the General Synod voted on GS2289, the Bishops’ response to LLF, a time of prayer was spontaneously called for. Maybe the orthodox should walk out in such a situation- few things can embody “spiritual partnership” more than corporate prayer. Alternatively, perhaps they should stay and lead in prayer that the revealed will of God would be honoured while others, in their turn, pray the opposite. Or perhaps the faithful should pray but then walk out? It would be a bold person who believed they could discern definitively which would be the right course of action.

Rt Revd Ric Thorpe, a suffragan bishop in the Diocese of London voted against the Bishops’ response to LLF, but his diocesan, Rt Revd Sarah Mullally voted for it. Anyone entirely boycotting “spiritual partnership” in that diocese might want to boycott any Bible teaching – whether given by him or her. Then again, those wanting to show their support for Thorpe’s sharing of their orthodoxy might determine that the last thing they should do is treat the two bishops the same. Of course, quite legitimately, some may take one approach and some the other, but that does rather serve to underline the difficulties.

A second principle is to consider the content of the agenda for clergy chapter meetings or clergy conferences – and avoid those parts that are, “more spiritual than temporal”. How such a judgement might be made, by whom and on what basis is presently unexplained. The decision could be made on the basis of the preponderance of agenda points or on the relative importance of some (sub-) points compared to others. Presumably, if a discussion develops down unexpectedly 'spiritual' lines any former judgment will have to be revisited, as will it if it transpires that what was thought to be an essentially 'temporal' agenda item is thoroughly inter-related to a 'spiritual' one. AOB might turn out to require some quick thinking!

Interestingly, this principle does not appear to apply to involvement in the Diocesan Board of Finance, Archbishops’ Council, Vacancy in See Committees or any form of synodical government. Here there is an explicit encouragement to be involved at the highest levels, in both spiritual and temporal matters.

Given that engaging with the diocese on spiritual matters is appropriate in some circumstances, it is necessary to return to the principle of ‘full spiritual partnership’. What indicates ‘full spiritual partnership’ as opposed to “partial spiritual partnership’ is hitherto unclear. Perhaps a certain percentage threshold will be required, or a scale applied. On reflection, it is not, in fact as obvious as might be assumed, that biblically there is such a ‘thing’ as ‘full’, or ‘not-full’, ’spiritual partnership’.

However, to maximise the effectiveness of the temporal/spiritual approach, and to help the House of Bishops to understand the seriousness of the matters at stake, unanimity within each, and uniformity across the 42 dioceses, would be of great assistance. How that could begin to be agreed and co-ordinated locally and nationally, week by week would, surely, defy the very finest of organisational minds.

In short, whatever the individual person or local church believes, the diocese clearly understands itself, not as a temporal estate agent but as the defining spiritual entity in the area and it operates itself on that understanding. How an alternative understanding can function within that is, to say the least, challenging.

The canonical position and the practical outworking of the local church’s relationship with the diocese confirm each other - the diocese is not merely secular in theory or in practice, nor in form or in functioning.

Bringing it all together

Six other thoughts, applicable across the above scenarios, are perhaps the proper place to conclude.

First, the battle is primarily not a political one but a spiritual one. It is not against flesh and blood but against the spiritual forces of evil. That supreme spiritual reality must, however, be lived out thoroughly practically, 'temporally'.

Second, Anglicans are not Greek Gnostics. Anglicans do not believe that the Lord is only concerned with an individual’s personal spiritual understanding. The confession recalls, “…we have sinned against you in thought, word and deed, by what we have done and what we have left undone”. The Holy Spirit dwells within the Christian’s body, whether they are engaged in a secular or a spiritual activity – which is why issues of sexual intimacy are so important. We cannot, therefore relate to anyone in a purely 'temporal' or 'spiritual' way.

Third, and following from that, as Christians offer their lives in living sacrifice, as a spiritual act of worship, they normally do everything they can to avoid the suggestion of any divide between the sacred and secular. The same chairman of ReNew quoted above has written,

“If we think we are somehow closer to God in our meetings on Sunday than we are when we are in our office, or on the sports pitch, or in the pub, then we have not properly understood the gospel.”[3]

“If in the workplace we are so consumed by the everyday detail of doing our job that we fail to see that our office is God’s harvest field, then we are no different to the disciples in John 4:31”.[4]

“For many of us we will carry on ploughing away in the secular work that we have been given to do, seeking to be godly. That, too, is a great thing to do: it is dignified, necessary and responsible. We are serving the Lord Jesus as we do so.”[5]

If the layperson cannot divide themselves, their attitude, or their time between the 'spiritual' and 'temporal' at work, in the home or pub, it is somewhat difficult to see how they can do so when they go, for example, to diocesan synod.

Equally, if a lay person cannot so divide themselves, it is not easy to envisage how a bishop could be asked to do so in their workplace and doing their job.

Fourth, the 'temporalities' and 'spiritualities' referred to in the Canons do not map easily onto any form of suggested temporal/spiritual divide. Since 1976, the 'temporalities' vested in the incumbent, include the church and churchyard and little else - a Priest-in-Charge, or curate, has no 'temporalities'.

Fifth, albeit concerning different orders of issue, it is something of an oddity to address a novel innovation in ethics with a novel innovation in ecclesiology. It is quiet rightly said that a such radical ethical innovation requires much deeper and wider consideration than it has been given and it might be thought that the same applies to a substantial departure from accepted ecclesiology.

Finally, even if elements of this blog are wrong, and even if the 'temporal/spiritual' divide could be made to function in the optimum way, it might be wondered if it is sufficient to address the gravity and extent of the current false teaching. That is all the more true if and where, at best, it leaves clergy and laity without any 'spiritual' episcopal oversight at all.

May the (good natured) discussion commence!

This article is well written - it is clear and biblical. The author is advocating that the division between spiritual and temporal non-spiritual which distinction arguably forms a basis for clergy to remain in the CofE is a fiction or fictitious divide that is not supported by or existent in Scripture despite its advocates in presently the so-called ‘Alliance’ evangelical churches.

However, notwithstanding this excellent article shedding or focussing light on what is true, I believe that if a CofE clergy truly desires to stay in the CofE, he will always find ways and means, to justify remaining by reference to seemingly impossible consequences of departing.

However, since God calls us in His Word to have nothing to do with…

May we have the name of the author of this article please?

After reading this I am not at all clear what the author is advocating.

When I worked in business, I was reluctant to write or speak about problems unless I also had at least an idea for their solution as I felt that I was in danger of griping or of being happy to put an issue into the 'too hard' box.

So, in the case of false doctrine being preached, what is one to do? You may be in the happy position that I am of having an orthodox diocesan bishop who voted against the proposals of the House of Bishops. But even then our Parish Share goes to fund other dioceses (via the national church) who teach falsehood…