Gafcon, ACC or Rome? Take your choice.

- Anglican Futures

- Nov 1, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Nov 3, 2025

Most historians would agree that the English Reformation took place over a century or more. There were moves and counter-moves along the way but looking back certain moments are still remembered as having particular significance.

One of those moments took place 470 years ago, on October 16th 1555, the day when Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley were burned at the stake in Oxford.

Both Latimer and Ridley had been ordained in the Medieval Church, under the jurisdiction of the Pope in Rome. Yet, Latimer described how he, “began to smell the Word of God, and forsook the school doctors and such fooleries". Both became fervant preachers and teachers of the Reformation and were made bishops of the English church. However, when Queen Mary came to the throne, Parliament repealed the laws which had separated the English Church from Rome, and in 1555, Cardinal Pole, the Pope's representative, absolved England of "all heresy and schism", so welcoming the 'English' church back into 'the' Church of Rome.

That Autumn, Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley were led to their deaths, and in the following Spring, Thomas Cranmer followed. Their memorial explains:

"To the glory of God and in grateful commemoration of His servants, Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Prelates of the Church of England, who, near this spot, yielded their bodies to be burned, bearing witness to the sacred truths which they had affirmed and maintained against the errors of the Church of Rome; and rejoicing that to them it was given not only to believe in Christ, but also to suffer for His sake.”

Tradition maintains that as the flames were kindled, Latimer turned to his friend and said:

"Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man; we shall this day light such a candle, by God’s grace, in England, as shall never be put out."

The flames of the Reformation did not go out, the Church of England was re-established and by God's grace the reformed catholic faith spread throughout the world, eventually leading to the establishment of the very Anglican Communion, which is now under so much pressure.

It may be that historians look back on October 2025 as one of the decisive times in the life of the Anglican Communion, not because of one particular moment but because of the coming together of a number of significant events that together changed it forever, for good or bad.

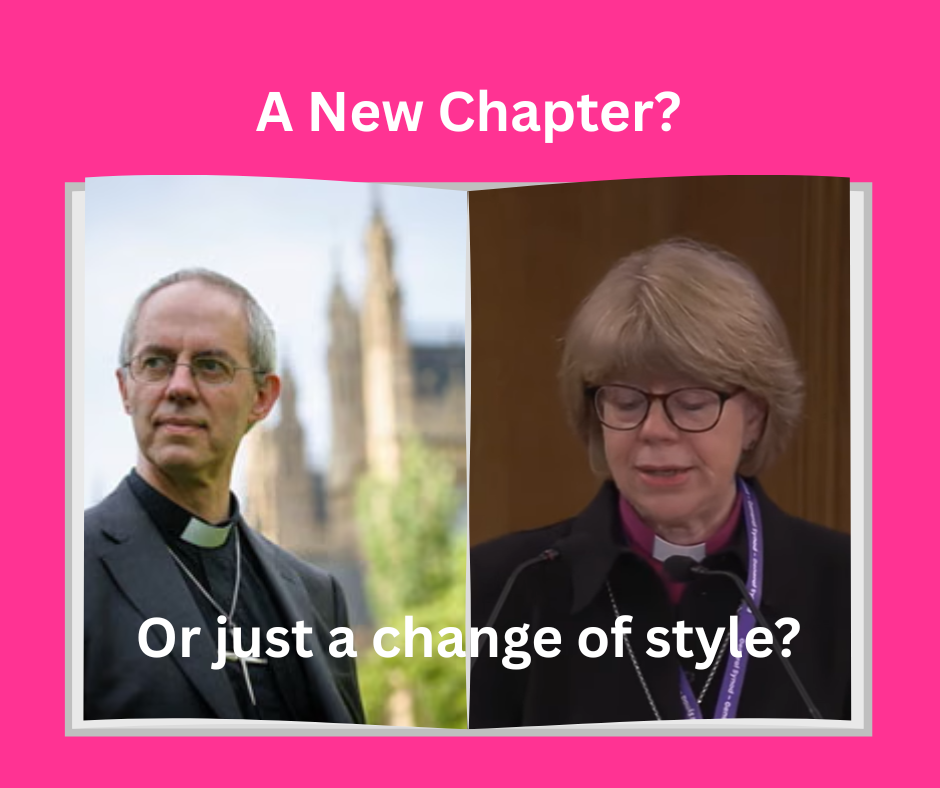

3rd October - The appointment of the first female Archbishop of Canterbury, The Rt Revd and Rt Hon Dame Sarah Mullally DBE was announced.

15th October - The House of Bishops of the Church of England issued an Update on Living in Love and Faith. They admitted legal and theological advice means further synodical processes will be required before introducing stand-alone services of blessing for same-sex couples or allowing clergy to enter into same-sex civil marriages.

16th October - Gafcon announce the Instruments of Communion are broken and as they are the Global Anglican Communion they will take the lead.

23rd October - allegations of sexual misconduct and bullying by the Archbishop of the Anglican Church of North America, Most Revd Steve Wood, hit the headlines.

23rd October - King Charles and the Archbishop of York prayed with the Pope in the Sistine Chapel - for the first time since the Reformation.

It is obvious that the Anglican Communion faces both internal and external challenges. Internally, decades of doctrinal wrangling, caused by provinces espousing increasingly 'progressive' theology and practice, has caused chaos. Externally, the momentum of the ecumenical movement has downplayed the importance of the Reformation in the popular imagination. This two-pronged attack, if allowed to succeed, could douse the candle lit by the Oxford Martyrs.

Internal Pressures

The appointment of a 'progressive' Archbishop of Canterbury, one who led the introduction of the Prayers of Love and Faith and sees them as a 'hope' for the Church, has turned up the heat on the decades long conflict within the Anglican Communion. What little hope there had been that a conservative Archbishop might appear on the horizon and bring order and discipline to the Communion vanished when it was announced that the Rt Revd Sarah Mullally would sit on the Chair of St Augustine.

To blame her for what may happen during her archepiscopacy would, however, be unfair.

In response to the dangers of Papal authority, the Anglican Communion is not a single 'Church' ruled by one 'Super-Archbishop' - instead there are more than forty churches and each one is autonomous, led by their own bishops and archbishops, and governed by their own synods. Order is meant to be overseen by four 'Instruments of Communion'. The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primus inter pares, a role with significant historic and moral 'soft' power and the ability to call meetings of the other three, the Lambeth Conference, the Primates Council and the Anglican Consultative Council (ACC).

These Instruments have proved entirely inadequate in the face of a few small but powerful provinces, which have sought to drive a coach and horses through Anglican doctrine and polity. Over the last thirty years, these provinces have insulted those who warned them of their error, and ignored their pleas to return to the faith once delivered. These provinces have defied the resolutions of the Lambeth Conference, defied the discipline of the Primates Council and have prevented the ACC from functioning as anything more than a talking shop.

In response, successive Archbishops of Canterbury have also failed - at key moments, Carey and Williams chose to passify the powerful progressive provinces rather than uphold traditional Anglican doctrine. While Welby's commitment to plural truth and his determination to 'walk together,' without meaningful discipline, have left Mullally standing on very shaky ground.

It is universally acknowledged that the Instruments of Communion are no longer fit for purpose - but there are diammetrically opposing views of what should replace them.

ACC - a future based on shared history

In the Nairobi-Cairo Proposals, the ACC suggest tinkering with the status quo. They propose a redefined relationship between provinces of the Anglican Communion and the creation of a 'rotating presidency' for the ACC, elected by those attending the Primates' Meetings.

While well-meaning, the Nairobi-Cairo Proposals fall into the trap set by the spirit of our age. It is a trap that Archbishop Runcie warned against at the Lambeth Conference in 1988 when he warned against the "shibboleth of autonomy" and predicted that the Communion had to choose between "unity or gradual fragmentation". The ACC have in effect chosen autonomy - each Anglican Church will be free to determine their own 'faith' as set out in their own prayer book, and they no longer need to be in communion with one another or with the Archbishop of Canterbury.

At the same time, the ACC rightly prizes the visible unity of the Church but this causes them to believe that institutional unity, despite serious doctrinal differences which prevent communion, is better than division. They envisage overlapping networks of autonomous churches, some in full communion with one another, others not, and many sharing stronger relationships with non-Anglican churches than with one another.

The Nairobi-Cairo proposals have to look backwards rather than forwards for any truly unifying factor– to the shared colonial history rather than the future mission of the church. In their attempt to be generous and humble, faith becomes an inheritance that autonomous provinces have the freedom to squander rather than pass on whole to the next generation. And the only requirement for continued membership appears to be the willingness to meet to discuss increasingly diverse theological positions, with an ever increasing number of churches, without judgement.

At a provincial level, these are also the issues with which the Church of England is wrestling. Progressive bishops have sought to push doctrinal boundaries and actively campaign for change, while conservatives have created their own pseudo-structures, in the hope that eventually they will be allowed to have an autonomous 'church' within the Church of England.

Yet, this month, the Bishop of Manchester explained why such a future has been rejected by the bishops, requiring as it does, “such a high level of delegation of episcopal ministries as to render, in the view of many bishops, such violence to our ecclesiology as to make it arguable as to what extent we could still be considered a single church. Whilst some on both sides of the LLF debate have indicated a willingness to accept such a stark division, it is not something which the House of Bishops has felt able to sanction. The role of bishops as guardians of the unity of the church, compels us to resist further disintegration.”

Just like the ACC, the bishops have allowed institutional unity to trump doctrinal discipline – with bishops claiming to be the focus of unity in and of themselves rather than by their call to teach truth and drive away error.

This in turn will lead to chaos. Progressive clergy have said publicly that they will defy their bishops and conservatives have done the same. The Revd Vaughan Roberts of The Alliance told the Pastor’s Heart, “I've always felt that the only way there's likely to be change is that if the alternative seems worse than giving up some kind of jurisdiction and I'm confident that the alternative will be worse because the Church of England will just be ungovernable. It will break down. But that'll take a while to play out.”

It seems likely that the Church of England will follow the path of those who have abandonded the reformed roots of the Anglican Communion. These provinces are in the main, small, white and western. Their congregations are ageing and some are on the verge of extinction. For all their talk of being progressive – they have very little to offer a new generation seeking meaning and something bigger than themselves.

Gafcon - a future based on shared faith

Gafcon offers something different.

In 2008, recognising the crisis that faced the Anglican Communion, bishops, clergy and laity gathered in Jerusalem –from all corners of the earth. They came to the Global Anglican Futures Conference to pray, to consult and to seek direction for the future. Their goal was to reform, heal and revitalise the Anglican Communion.

Gafcon has consistently declared that it is the doctrinal foundations, not relationship with the Archbishop of Canterbury, that must define our core identity as the Anglican church. These foundations are not 'new' but

The Jerusalem Declaration, agreed in 2008 by one of the largest gatherings of global Anglicans, set out the basis of fellowship – the bounds of that reformed catholic faith inherited from Latimer, Ridley and Cranmer. Since 2008, Gafcon has called on provinces, dioceses, parishes and individuals to join them in affirming these truths and proclaiming the gospel faithfully to the nations. They have also called on those who reject them to repent.

Nearly twenty years later there is no sign of repentance from the breakaway provinces and instead the errors have spread and the tear in the fabric of the Anglican Communion has grown wider and deeper.

Meanwhile Gafcon has continued to be an Anglican fellowship, an Anglican communion that is diverse, youthful and growing. The shared faith, has led to shared mission, as new partnerships have sprung up between dioceses and parishes. Gafcon have provided a home for more than a million dispossessed Anglicans whose own provinces have departed the faith once delivered - in North America, Brazil, Europe, New Zealand and Australia – and in doing so they have united them with the vast majority of the world’s Anglicans.

It is no coincidence that Gafcon published their latest statement on the 15th October - as it is the day the Anglican Church remembers the deaths of Latimer and Ridley. It simply represents another step on the path that began in 2008 - for the Anglican Communion to survive they say, order must be restored. Like the Reformers before them, they realise that order must be determined by the inerrant word of God, “translated, read, preached, taught and obeyed in its plain and canonical sense, respectful of the church’s historic and consensual reading.”

The Statement also rejects the old order, represented by the Instruments of Communion, because, far from upholding the word of God they have become a place where error and truth are celebrated alongside one another making discipline impossible. The sneering anger from progressive commentators about the very idea that the word of God should be the supreme authority in the Anglican church reveals just how far they have travelled from the faith of Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley.

Gafcon is clear that they are not going anywhere - for they are the ones who are standing firmly in the same place – it is the others who have sailed off into the sunset. In this there are echoes once again of their Reformation roots, as Richard Littlejohn, Director of the Davenant Institute, said, in a lecture given in 2019,

"Theologically speaking, Hooker’s answer is a pretty straightforward one. The church is first and foremost a theological entity, not a sociological one, defined by the Lord who names it and the faith that claims Him as Lord. The full catholic church that transcends time and space has many members, some of them more and some of them less sound. To separate from corruptions—and if necessary from corrupt members—is not to separate from the one holy catholic church, but on the contrary, to reaffirm one’s commitment to and union with her. On the Protestant account, which Hooker cheerfully endorsed, it was really Rome that had become un-catholic on many points."

As others have said, Gafcon's 'Global Anglican Communion' will need to guard against pride, division and personalities, they will need to have effective means of discipline, as will their individual churches, and the Primates Council will need to avoid the loss of the conciliar spirit that has permeated past conferences. Conversations with the Global South Fellowship of Anglicans, who are committed to a covenantal approach to the discipline in the Communion may still bear fruit, and there is always the continued desire that through repentance and a return to the apostolic faith all will be one.

All this will take time - but the Martyr's Day Statement is not the first word and nor will it be the last.

Meanwhile in Rome

As if the internal challenges were not sufficient, the events of October 2025 raised questions about the need for the Reformation at all. King Charles' decision to pray with Pope Leo, in a very public and very staged ecumenical service in the Sistine Chapel, was reported in The Tablet as, “...far from a mere gesture but a statement of an ardent desire for that unity which Christ commands."

This was not merely a state visit. It is not possible for the King to put aside his role as 'Defender of the Faith' or 'Supreme Governor' of the Church of England on such a visit, as the Revd Dr Ian Paul has suggested, and is even harder to countenance that this was purely 'political', when it was not just the Foreign Secretary who accompanied Charles to Midday Prayer, but also the Archbishop of York. Similarly, the symbolic honours that were swapped had religious rather than civil titles and were described by Buckingham Palace as, "a recognition of spiritual fellowship."

While Revd Dr Ian Paul has set out very clearly some of the "significant" doctrinal differences between the Roman Catholic and reformed catholic faith, he underestimates the impact of the ecumenical movement on the way such differences are perceived.

One of Justin Welby's first acts as Archbishop of Canterbury, was to install the Community of Anselm at Lambeth Palace, a community which is described by the Roman Catholic, Pontifical Council of the Laity as, "a Catholic community with an ecumenical vocation which is also open to the faithful from other Churches." Of course, if pressed they would suggest that 'the faithful' are those who accept the unreformed Roman Catholic faith.

Similarly, Justin Welby believed it was "the events of the Reformation and the history since," rather than the deep doctrinal differences, that means "it remains impossible for Anglicans and Roman Catholics to receive communion together". In a carefully worded statement he and the Archbishop of York spoke of "the lasting damage done five centuries ago to the unity of the Church", and called for people,"to repent of our part in perpetuating divisions."

As the Rev Dr Ian Paul concludes,

"Jesus’ prayer for unity was not about ‘full visible union’ between two institutions. It was that God would unite his followers together by ‘sanctifying them in the truth; your word is truth’ (John 17.17). Until we can agree on the truth about the completeness of Jesus’ work on the cross, that in Communion we remember him and ‘feed on him in our hearts by faith’, and that it is Scripture as ‘God’s word written’ which is our authority, we will not be fully at one."

Which brings us back to the start of this blog.

Reformation takes time - and over the coming decades the Anglican world will be re-ordered. But the events of October 2025 mean that, if a return to Rome is not on the cards, there are now two clear choices:

On the one hand the ACC offers a re-ordered 'Anglican Communion' - where visible, institutional unity is prioritised and found in little more than shared history.

On the other Gafcon offers the re-ordered 'Global Anglican Communion'- where unity is found only in submission to God's word.

The choice that faces each faithful Anglican is to decide which vision offers the best hope of keeping alive the candle lit by Ridley and Latimer?

To discuss the issues raised by this blog,

join us online on the 13th November for our regular

Close to the Edge gathering.

GAFCON Ireland are not inspiring. Bishop David McClay failed to formally name a deceased paedophile cleric who is buried by a cathedral entrance with the tombstone ending PRIEST SHEPHERD FRIEND........

Some scattered early-morning thoughts coming up...

Do the recent challenges about culture and alleged abuse in ACNA, in the light of our own issues with Titus Trust, Emmanuel Wimbledon, Soul Survivor etc., have anything to teach us / warn us / show us about pathology and problems in our own "tribe" culture?

Also, am I right in saying that AMiE etc is made up only of people who are what we would call conservative evangelical (Titus-Trust-Proc-Trust-Gospel-Partnership types -- and I write as someone from that stable)? Does that reflect a spiritual pride and inability to work with others? Or that others are turned off by something they see in us? The gospel partnership ministry training course I attended 15 years…

"Carey and Williams chose to passify the powerful progressive provinces" - if only they had indeed passified (rendered passive) them instead of pacifying (appeasing) them

"As the Rt Rev Dr Ian Paul concludes" - may I be the second to congratulate Mr Paul on his recent consecration?